Echoes from the Uplands: Understanding ancient upland cultural landscapes

Dive into new archaeological observations and discoveries made within Appalachian upland landscapes. This page describes site location settings within the uplands, and the potential significance for some of these findings, both to the general Public and to ancestral Tribes

QUARRIES

CINAQ: What is a Native Quarry?

*A site where Native/Indigenous peoples extract(ed) raw rock or mineral material for human use.

*Raw materials are then processed in a quarry workshop.

*Uses include projectile points, edged tools, quarrying picks, hammerstones anvils and wedges.

*Native quarried materials were traded widely across the America's

South Appalachian uplands and Native American (pre-European) stone quarries- Ancient cultural impacts and landscape alteration.

Explore an array of Appalachian pre-European quarries, many of which are scattered across upland landscapes at varying elevations. As explained by Dr. Philip LaPorta with the Center of the Investigation of Ancient and Native Quarries (CINAQ), these significant site types offer unparalleled insights into the sophisticated resource extraction and technological prowess of ancient peoples, demonstrating a rich history of engineering and collective labor, long present before the arrival of Europeans. The scale and complexity of quarries can be comparatively breathtaking, and their archaeological contexts will be critical for understanding the underlying significance for ancient, complex and large-scale Native American resource extraction efforts.

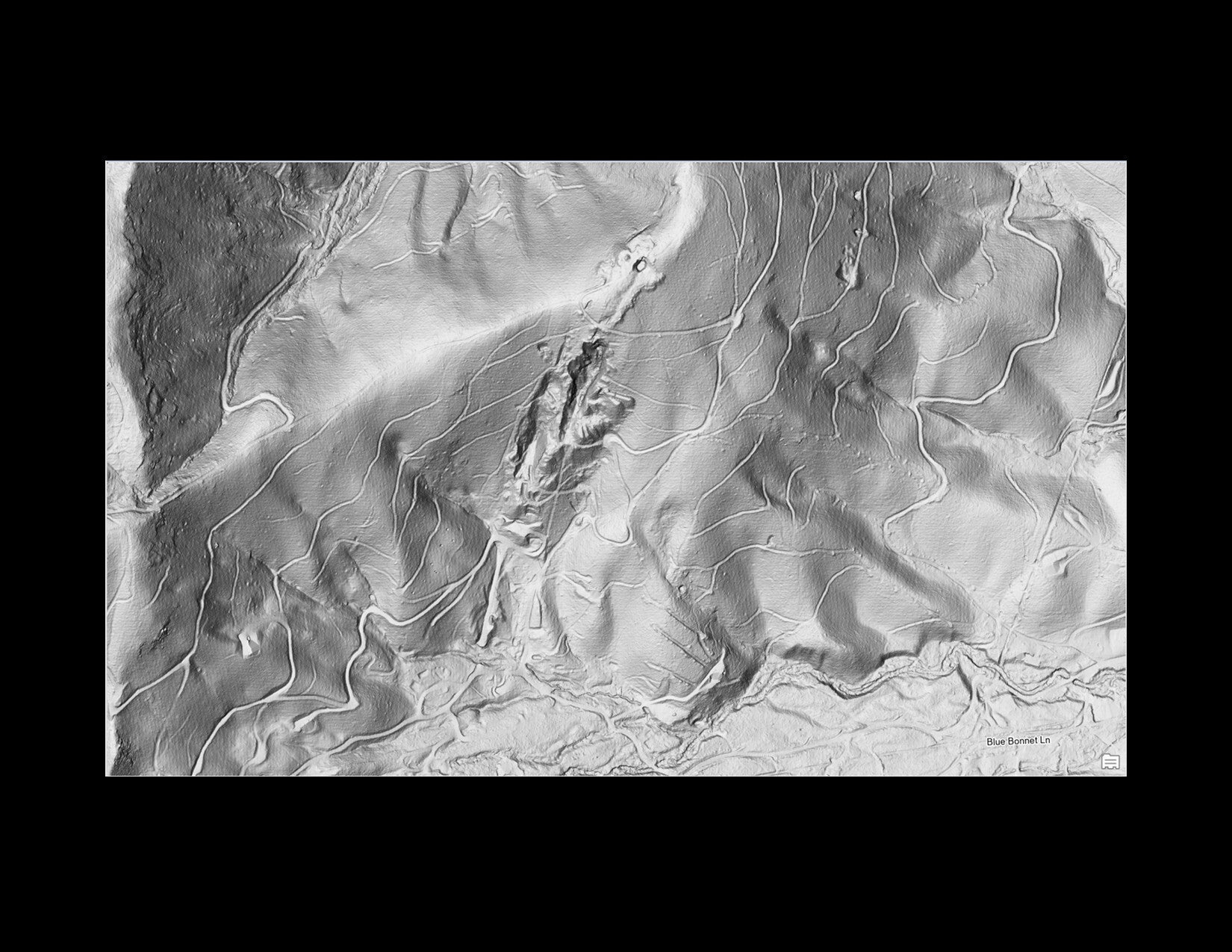

LiDAR Imagery Analyses

In the associated Figure, a Western North Carolina LiDAR hillshade image reveals a possible large pre-European Native American quarrying landscape, where local geologic conditions produce outcrops of high-quality “milky” quartz. The clustering of potential quarry zone signatures includes the gold-outlined polygons identified by Sas and Ashcraft through image analysis, as well as during extensive field reconnaissance conducted by Ashcraft (2023–2025); Ashcraft and Sas (2024, 2025); Ashcraft, LaPorta, and Minchak (2022); and Ashcraft and Kimball (2022).

Variation in landscape signature characteristics may reflect differences in underlying geology. The red dotted polygons mark areas that exhibit intermittent or ambiguous forms of hypothesized quarrying signatures but have not yet been field verified.

Identifying and evaluating these potential quarrying zones is best accomplished by a multidisciplinary team that includes experienced LiDAR specialists, upland geomorphologists, bedrock geologists, soil scientists, and archaeologists. Such collaboration allows quarry zone features to be examined in the field and collectively discussed, questioned, cross-checked, and—where appropriate—preliminarily interpreted. Until these upland quarrying and extraction signatures are better defined, interpretations of the evidence should rely on integrated, multidisciplinary assessment.

Are there distinct quarrying landscape signature types or forms seen in the evidence thus far?

(Under construction) Preliminary observations indicate that impressions left by extensive quarrying may be a direct result of the underlying geology and how the particular stone formation being extracted is positioned and its lineation or folding within the bedrock geology. It appears as if particularly metamorphosed, folded and stretched rock types like mylontinized quartz result with distinctive patterning of extraction methods that either follow highly accentuated natural drainages or the formation of its extraction trenches mimics heavily, deeply entrenched dendritic patterning. In these locations, its hypothesized that rain water was likely utilized for overburden removal and channeled down and out multiple trenches connecting downward to the main drainage features (Ashcraft and Sas 2025).

More recent, historic period quarrying and mining features

LiDAR hillshade imagery showing the distinctive landscape signatures that generally result from historic period quarrying or mining (American or early European activities). These operations typically occurred during the age of powered machinery and vehicles and their landscape signatures are usually easily discernable. From maps or LiDAR imagery, they can be recognized by dramatic and deeply excavated extraction features, including long, deep trenches, vertical shafts or adits that extend horizontally into the sloping terrain. These more modern operations are generally accessed or surrounded with multiple road cuts into the side-slope or roads and skid-trails extend directly up/down the adjacent slopes to more formal transportation roadbeds. Historic era operations also very often overprint or destroy much earlier Native American quarrying or mining sites. These more ancient efforts were still visible on the landscape, such as mica mining signatures, and often were easily recognizable during historic prospecting and recon operations (under construction)